EACHDRAIDH DUNLOP

FOOTSTEPS OF OUR CLAN

Here be True Stories of Our

Namesakes…

Read, And Walk With Them Through

Time.

How John Dunlap placed our Name on the most famous

government document of all time.

By Mike Dunlap, Clan Historian

In Strabane, Northern Ireland, around 1746, a

young lad of ten years prepared to leave on a transatlantic journey. He had

learned some of the printing business at Gary’s Printery on the Earl of

Abercorn’s estate, a well-established publishing and printing center in the 18th

century. Now he was to join his Uncle William, a printer and publisher in

Philadelphia as an apprentice. His grandparents had come from Scotland nearly

fifty years ago for a life in another country, and now he was to leave theirs

and go to a New World.

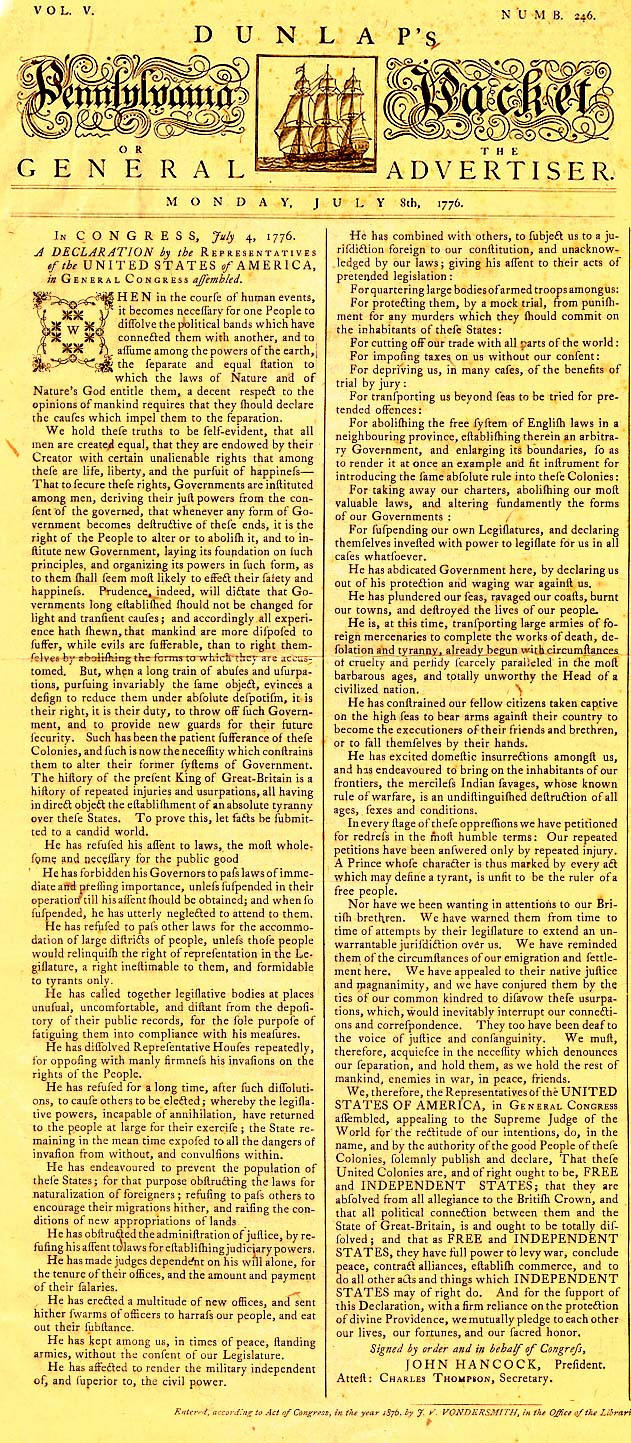

When John Dunlap became eighteen, he took over

the business from his uncle, who had become a Minister. He began publishing a

weekly newspaper, The Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser.

This weekly soon became known as a reliable source for news concerning the

Continental Congress. John married into a Patriot family, with his new great

uncle being Benjamin Franklin himself!

On a hot July day in

Philadelphia, 225 years ago, John began the most important “rush job” in all

history at his shop at 48 High Street. He was to print a “broadside”.

Broadsides- single sheets printed on one side- served as public announcements or

advertisements from the beginnings of printing in America through the early 20th

century. Generally posted or read aloud, broadsides provided news of battles,

deaths, executions, and other current events. They were popular “broadcasts” of

their day, bringing news of current events to the public quickly…. and often

disappearing just as quickly.

Fighting between the American colonists and the

British forces had been going on for nearly a year. The Continental Congress had

been meeting since June, wrestling with the question of independence. Finally,

late in the afternoon on July 4th, 1776, twelve of the thirteen

colonies reached agreement to declare the new states as a free and independent

nation. New York was the lone holdout. John Hancock ordered Philadelphia printer

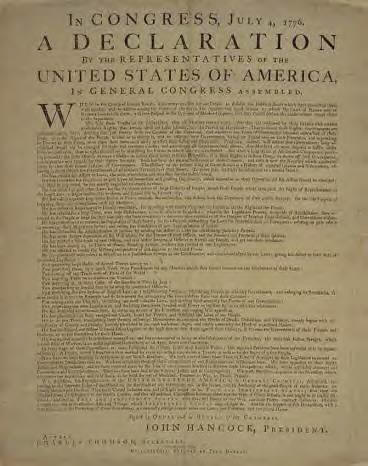

John Dunlap to print broadside copies of that declaration that was signed by him

as President and Charles Thomson as Secretary.

“Benjamin

Franklin himself approved the layout set up by Dunlap. The Caslon type was

elegant, the headlines bold and arresting. The Colonies’ point-by-point list of

outrages committed by King George III and his mercenary army spread across the

page in a single column with almost biblical thunder. With only the rough draft

written by Jefferson and approved by the Congress as a source, Dunlap configured

the broadside to assure the greatest impact, and then added his own name to the

bottom: “Philadelphia- Printed by John Dunlap”. If the Revolution failed, he

would hang with Franklin, Jefferson, Adams, Hancock and the rest!”

Two to five hundred

copies were printed that July evening. The next morning the first copies were

distributed to members of the Congress and riders were sent throughout the

colonies with John’s documents in hand. On July 8th independence was

publicly proclaimed in Philadelphia. On the ninth, General George Washington

read the Dunlap Broadside aloud to his troops to raucous cheers. Printers

throughout the colonies copied the document and word spread very quickly that

America was free!

The Dunlap Broadside was, in fact, the first

printed copy of the Declaration of Independence. The more familiar

hand–engrossed Declaration was not completed until August 2nd, 1776,

when the delegates assembled to affix their signatures. By then Dunlap

Broadsides had reached public assemblies in all thirteen colonies, and many

British military headquarters.

John went on to become the official printer for

the Congress, and the Packet became the first daily newspaper in the

United States. He died a hero and a veteran, having founded and captained the

1rst Troop of Philadelphia City Calvary, used as bodyguard for General

Washington at Trenton and Princeton.

There are only twenty-five copies remaining of

the original broadside and twenty-one of them are owned by museums or libraries.

The last to be found was in 1989 by a man browsing in a flea market who bought a

painting for $4 because he wanted the frame. Concealed behind the painting was

an original Dunlap Broadside of the Declaration of Independence. Sotheby’s

auctioned this copy for $8.4 million in the spring of 2000. Its message was

worth much more to the people of 1776 and immeasurably more today, in 2001.

The Footsteps

of our Clan walk across the Declaration of Independence

and our name

resides proudly there!

Merito!

Source:

http://www.thedeclarationofindependence.org/hallofthehistoricarchives/DUNLAPBROADSIDE.NET/

John Dunlap

1747 - 1812

Printer and Patriot

DUNLAP, John, printer, born in Strabane, Ireland, in 1747; died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 27 November, 1812. While a boy he went to live with an uncle, William Dunlap, a printer and publisher in Philadelphia, at the age of eighteen entered the business, and in November, 177I. began the publication of the "Pennsylvania Packet." This paper was changed into a daily in 1784, the first in the United States, and afterward became the "North American and United States Gazette."

Mr. Dunlap was

appointed printer to congress, and first printed the

"Declaration of Independence." He was an officer in the first troop of

Philadelphia cavalry, which became the body-guard of

Washington at Trenton and

Princeton. In 1780 he gave £4,000 to supply provisions to the Revolutionary

army.

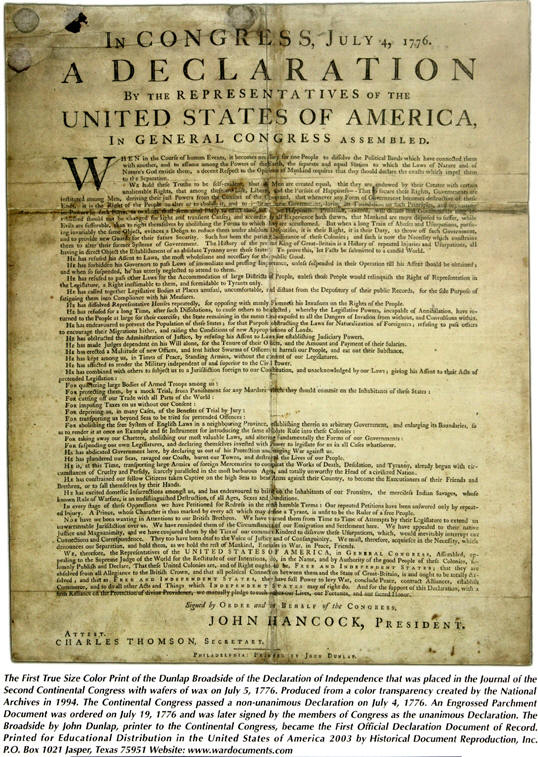

The Dunlap Broadside

Also known as the first printing (July 4, 1776) of the American Declaration of Independence.

The Dunlap broadsides

were the first printed copies of the Declaration of Independence. The term

broadside refers to a sheet of paper printed on one or both sides, much like a

newspaper page or a poster today. The average size of a Dunlap broadside is

about 20 inches high and 16 inches wide.

Congress ordered the

Declaration of Independence printed and late on July 4, John Dunlap, a

Philadelphia printer, produced the first printed text of the Declaration of

Independence, now known as the "Dunlap Broadside."

Early on July 5, about 200

broadsides of the text were printed at John Dunlap's shop.

The next day John Hancock, the president of the Continental Congress, began

dispatching copies of the Declaration to America's political and military

leaders. They

were rushed to the 13 colonies and to the army to be read aloud to the people.

On July 9, George

Washington ordered that his personal copy of the "Dunlap Broadside," sent to him

by John Hancock on July 6, be read to the assembled American army at New York.

On July 8, 1776, Colonel John Nixon read the

Declaration of Independence in the State House yard.

On July 19, Congress ordered the production of an engrossed (officially inscribed) copy of the Declaration of Independence, which attending members of the Continental Congress, including some who had not voted for its adoption, began to sign on August 2, 1776. This document is on permanent display at the National Archives. In 1783 at the war's end, General Washington brought his copy of the broadside home to Mount Vernon.

Of the 25 surviving Dunlap broadsides, 21 copies belong to universities, historical societies, public libraries, and city halls; and the remaining four are in the hands of private owners and foundations. One of the surviving Dunlap broadsides is on view as part of a tour known as the Declaration of Independence Road Trip.